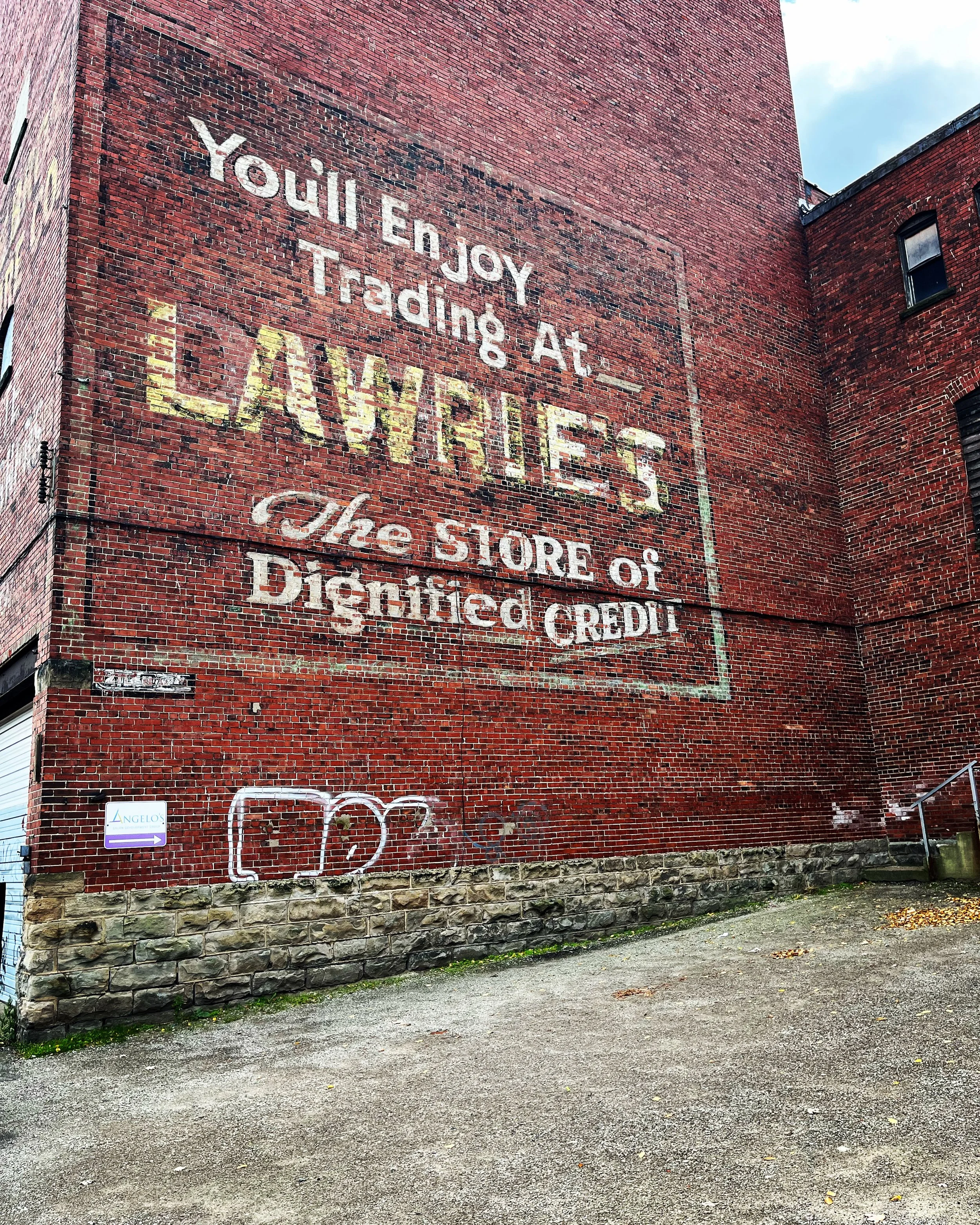

Hidden History

Beneath the surface of Erie’s familiar streets and quiet corners lies a hidden archive of stories long forgotten. This is your guide to the overlooked relics and whispered echoes of history scattered across the landscape—those rusted plaques, faded foundations, and silent monuments we pass daily without a second glance. This project uncovers the secrets etched into Erie’s soil, inviting you to see your surroundings not just as scenery, but as a living museum of mystery and memory.